CLYDE McPHATTER

If any one man can be given credit for actually inventing rock 'n' roll singing it is Clyde McPhatter. As a 20 year old lead vocalist of the Dominoes in 1950 he used his gospel background to create an entirely new and unique style within secular recordings, stating he preferred to "take liberties with the melody" rather than adhering to what was written. The result was startling in its power and reach as he could turn simple heartbreak into anguished torment or radiant joy into pure ecstasy, something downright shocking in an era known for smooth vocal crooners and tight-knit, strictly by the book, harmonies. By contrast the Dominoes records were dynamic affairs with McPhatter's soaring tenor out front backed by wailing saxes and jumping vocal support. Even the ballads were emotional powerhouses as he'd wring out every ounce of drama from them until both he and the listener were drained. The group was such a sensation that McPhatter routinely created hysteria among the females in the audience during his tortured performance of "The Bells" night after night.

His three year run fronting the Dominoes resulted in nine Top Ten hits, including two of the biggest #1 smashes of all-time, "Sixty Minute Man" and "Have Mercy Baby", which reigned for a combined twenty-four weeks in the top spot on the R&B charts. In March of 1952 the group headlined the first major rock 'n' roll concert ever given (Alan Freed's Moondog Coronation Ball in Cleveland). The show erupted into a full scale riot almost before it began and the resulting public outcry over it helped to forever seal rock's social status as a dangerous entity. Despite this nearly unrivaled success and overwhelming acclaim in the black community, McPhatter became increasingly frustrated with his lack of star billing and his status as a salaried employee to group founder, leader and songwriter Billy Ward, who ran the group with an iron hand. In 1953 McPhatter finally had enough of Ward's stifling control and quit the group, replaced by a young Jackie Wilson whom he had been grooming as his successor for months.

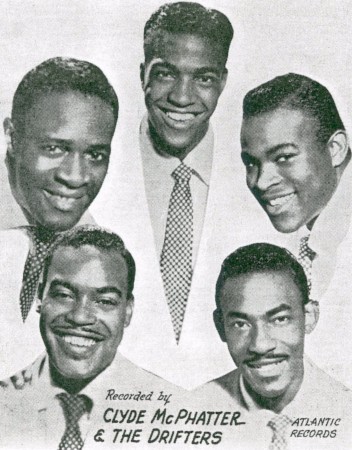

While the Dominoes following his departure abruptly veered away from the raw and raucous style they'd practically invented, consciously distancing themselves from their immediate past, McPhatter was only just beginning to cement his legacy by spearheading the even more drastic advances on the musical horizon. As soon as word spread of his contractual release from the group that made him famous Atlantic Records president Ahmet Ertegun offered McPhatter the chance to form his own group with Clyde guaranteed top billing and in the spring of 1953 The Drifters were born sending him to an even higher level of celebrity.

His two years with the Drifters came when R&B was crossing over into white teen awareness and being publicly rechristened "rock 'n' roll" in an effort to make the image of the music less racially stigmatized to an integrated audience. The Drifters set the stage for that cultural transformation with a series of scintillating songs fueled by McPhatter's incredible voice. Their debut, "Money Honey", topped the charts for 11 weeks, giving him the distinction of having sung on the biggest R&B hit for three consecutive years, something no other artist in the history of the American Pop and R&B charts has done since.

A year later the salacious "Honey Love", which he co-wrote, gave them another two month stay at #1 and actually crossed into the then nearly all-white Pop Charts, a rarity at the time, especially for a song that was banned in many places due to its explicitly sexual lyrics and suggestive, almost obscene, delivery. At this point there was no question remaining as to who was poised to be the biggest star in rock 'n' roll as it reached the masses, for McPhatter had it all the already devoted following, the support of the most forward thinking record label in the business, and above all else, vocal ability that was unmatched. He was held in the highest esteem by his peers, such as Fats Domino and Chuck Berry who were ardent fans of his, and Domino would even stand in the stage wings on tours with McPhatter to watch him sing each night. His future seemed truly limitless.

But it didn't last. Drafted by the Army in 1954 at the peak of his popularity, McPhatter had only one more recording session with the Drifters while on leave, resulting in the #2 smash, "What'cha Gonna Do", the melody of which was later adapted as the basis of "The Twist". The Drifters carried on in their personal appearances without him but upon his discharge in 1955 McPhatter sensed opportunity knocking to reach an even higher personal level of stardom and wasted no time in embarking on a solo career with the full backing of Atlantic Records, a move that seemed destined to pay off handsomly for all involved.

Clyde McPhatter in the Army

The stage was set for McPhatter to rise to unprecedented heights in 1955, for as popular as vocal groups had been when rock first began making inroads into the wider marketplace, it quickly became evident that solo acts were the better bet for rapid career advancement and maybe more importantly for the kind of personal recognition that all gifted performers crave. For McPhatter, who had suffered the indignities of his mentor Billy Ward trying to conceal and downplay Clyde's role in the success of the Dominoes, and then having to share the spotlight to a degree within the Drifters, a solo career offered the opportunity to receive all of the accolades due him for once and to have a greater degree of control in his own musical destiny than ever before.

Clyde McPhatter didn't set his sights low either, for it was his hope to become the first young black crossover star, able to appeal to both teenage rock fans of both races as well as to older pop fans and in the process take his place alongside the Perry Comos and Nat "King" Coles of the world as one of the biggest vocal entertainers in the business. But it was a case of misreading the landscape, as figures like Elvis Presley and Little Richard, both of whom were heavily influenced by Clyde, were leading the rock 'n' roll charge that would soon all but obliterate the old rules of the business, in the process forcing traditional pop to go the way of the dinosaur when it came to younger record buyers who were now the primary audience for hit singles. The kind of genteel tailored pop star that had once seemed infallible and held aloft as the pinnacle of success was now seen as yesterday's news, while the wild rockers, perceived as uncouth and uncontrollable to the older generation, were rapidly taking over the airwaves and steering the direction of popular music towards a frenzied new frontier.

Clyde McPhatter 1

McPhatter's efforts to combine the two vastly conflicting styles in his solo career compromised his material too much for him to fully overcome. His fervent rock 'n' roll fanbase were not as pleased with his pop concessions, his drastically toned down and increasingly mannered delivery along with the intrusive addition of syrupy female choruses on many tamer songs, while white adult society could not have cared less about a black superstar trying to reach out to them, no matter how talented he was. Furthermore, the bigger the rock audience itself became with each passing day, the more recent fans of their growing ranks had no idea of McPhatter's past glories with the Dominoes and Drifters that had created this style of music to begin with. They were only looking forward now, to each new artist and record that captured their fancy, and so unlike the audience that had started the rock 'n' roll boom this newer generation didn't even have the same connection and loyalty to him that would've at least sustained interest in what he was doing as he attempted to branch out. Consequently the more McPhatter deviated from the straight-forward rock material they craved, the more irrelevant he became to the ever younger rock audience. He still scored a number of hits with his more artistically pure performances throughout the next eight years, including his final chart topper, 1958's "A Lover's Question", showing that he was more than capable of delivering with the right material, but those types of records were becoming fewer and farther between and his once invulnerable reputation within the music industry began to slowly crumble.

Meanwhile both of his old groups were facing even tougher times. Billy Ward had taken the Dominoes even farther away from their racy beginnings and, like McPhatter, had hoped to conquer the traditional pop style that once had ruled the music world. Even with the astounding vocal talents of Jackie Wilson, the group floundered commercially the farther away from rock they got. Hoping to break into the still lucrative adult club scene they began playing Las Vegas casinos, most of whose audiences had never heard of their original greatness and wouldn't have liked that old style if they had, and the one whiff of mainstream success they craved came after Wilson had gone solo and Eugene Mumford sang lead for them on a comparatively tame version of the old standard "Stardust". It was a long way from Clyde's wild histrionics of "Have Mercy Baby".

The Drifters too faced diminishing popularity once Clyde left them. They managed to briefly hold onto their momentum with a series of McPhatter-styled replacements at the helm, including notching another #1 R&B hit in 1955 with "Adorable", but as time wore on they slowly began losing relevance without their charismatic and instantly identifiable lead. The frustration of having to try and connect with a new younger and whiter audience proved harder than anticipated and soon the group's core began to split up, with several members leaving, rejoining and eventually getting fired by the group's thrifty manager, until finally, in 1958, they were disbanded completely and an entirely new group of singers with a far different style were brought in to carry on the name and restore them to their former glory.

By the time the new Drifters hit the top again in 1959 with "There Goes My Baby", with Ben E. King on lead, McPhatter's own days as a star were mostly behind him and increasingly it seemed like there was no escaping the downward spiral of his own career. Changing record labels multiple times couldn't produce more than a few tantalizing glimpses to his past glories, 1960's "Ta Ta" going Top Ten R&B and Top 25 Pop, while 1962's "Lover Please" marked his final entry into the Pop Top Ten. Even with those successes fresh on his mind, proving that rock 'n' roll was the best avenue to follow, he stubbornly continued to try and achieve mature pop acceptance with outdated material and arrangements, insisting on strings and lush touches that neutralized his own greatest strengths as a singer and were almost guaranteed of being ignored by the larger rock audience. In the past when he had tackled standards with the Dominoes ("Harbor Lights") or Drifters ("White Christmas"), he had totally remade them in his own image, retaining only the barest essentials of the originals while imprinting them with his own idiosyncratic stamp. The results had been both aesthetically dazzling and commercially appealing to a young and enthusastic rock fandom. Now, incomprehensibly, he was hell-bent on abandoning that exhilerating style entirely and sought a return to the very type of music that his early work had helped send packing a decade earlier.

Clyde McPhatter 2

The frustrations of his dwindling sales, coupled with his growing anger over racial hostilities he and his fellow black performers still faced on the road, made Clyde all the more despondant and unstable. A fervent Civil Rights advocate, McPhatter was adament about organizing black performers to stand up to social injustice, including famously leading an artist boycott of a concert in which he and Sam Cooke grabbed headlines when they refused to perform in Memphis since the audience would be segregated by race. But the slow progress made across the industry and in society on that front, the increasing violence down south by racist whites in retaliation to even these gradual cultural changes and the apathetic reactions to racial unrest he saw up north, plus the overall pressures of having to balance that civic duty he felt was his obligation with the demands of a performer further chipped away at his emotional well-being and he began drinking more and more and consequently his musical output suffered greatly.

Clyde McPhatter 3

By the mid-60's his new records had largely stopped selling and he was forced to ignominiously record cover versions of hit songs done by the "new" Drifters as well as their other famous ex-lead singer, Ben E. King who scored big with his own recently launched solo career, in hopes of finding an unlikely hit by appealing to those curious about the intended irony of the situation. Even Clyde's own last Top 100 Pop hit, 1964's "Deep In The Heart Of Harlem", though a good song and performance, was little more than a quasi-takeoff on the Drifters current style. Although his live appearances still were popular with longtime fans who remembered him from when he ruled the early 50's R&B kingdom, promoters were growing tired of his erratic alcohol-fueled behavior and he began wearing out his welcome even in those venues. When his last record of note, the near-brilliant "Crying Won't Help You Now", done in a thoroughly modern uptown soul style that was ruling the rock airwaves at the times, fizzled out at just #117 on the Pop Charts, it seemed as if McPhatter was fast nearing the brink of irrelevance.

Faced with this unwelcome truth McPhatter subsequently moved to England where a new generation of fans were just discovering his legacy of a decade earlier and he was at least ensured fairly steady work in front of smaller, but at least fairly enthusiastic audiences which must have seemed a relief to him after years of declining interest at home. His personal outlook however remained increasingly bleak and trouble followed him wherever he went, eventually leading to an embarrassing arrest in Great Britian that all but ended his tenure as a viable live performer in that country as well. Even the few potential rays of hope that shone through in these days were quickly dimmed, as when one of his biggest admirers, Otis Redding, had plans to ask McPhatter to record on Redding's newly formed label in an updated style with Otis himself producing, only to see Redding die in a plane crash before the offer could be made. As the turbulant sixties drew to a close McPhatter's career and life were in tatters, so much so that when an interviewer approached him and began by saying what a fan she was of his, Clyde despondently replied, "I have no fans".

By the dawn of the 70's, sensing promise in the 50's rock revival that was sweeping America, McPhatter was determined to make a comeback, reuiniting with his old producer Clyde Otis and cutting new tracks in a last-ditch attempt to revive his career. He never got the chance to carry out those plans however, as an alcohol-related heart attack killed him at age 39 in June of 1972, silencing one of the greatest and most influential voices rock 'n' roll music has ever known.

Info :100 Greatest R'N'ROLL ARTISTS

Comentaris

Publica un comentari a l'entrada